The Shoddy workshop about Lorina Bulwer’s workhouse embroideries was a fascinating – and tantalising – session. It gave us a chance to find out about Lorina’s life and what it might have been like for her in the workhouse, but because a limited amount is known about her, we had loads of questions as well!

20 people came along to the workshop on 20th October 2016. It was part of the Love Arts Festival, which celebrates mental health and creativity. I wanted to do something during the festival that linked some of Shoddy’s themes with mental health, for example, use of textiles, looking at the lives of disabled people in the past and comparing this with things today. When I learned, while doing some research for Shoddy, that Leeds’ Thackray Medical Museum had one of Lorina Bulwer’s scrolls in their collection, this fit the bill perfectly.

20 people came along to the workshop on 20th October 2016. It was part of the Love Arts Festival, which celebrates mental health and creativity. I wanted to do something during the festival that linked some of Shoddy’s themes with mental health, for example, use of textiles, looking at the lives of disabled people in the past and comparing this with things today. When I learned, while doing some research for Shoddy, that Leeds’ Thackray Medical Museum had one of Lorina Bulwer’s scrolls in their collection, this fit the bill perfectly.

Lorina Bulwer lived much of her life (1838-1912) in Great Yarmouth. When she was 55 she was placed in the asylum of Great Yarmouth workhouse by her brother. It was here that she created a number of embroidered scrolls expressing her anger at her situation.

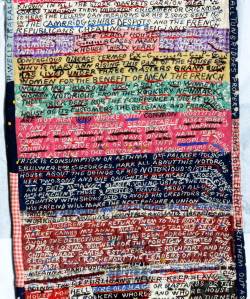

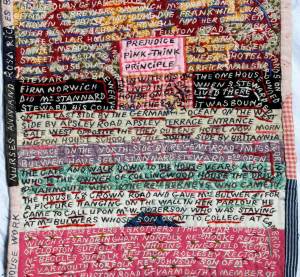

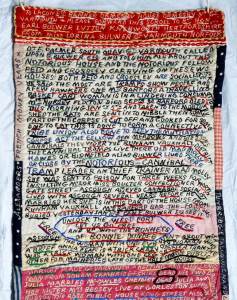

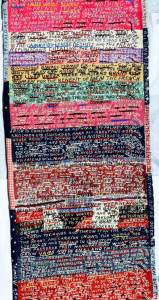

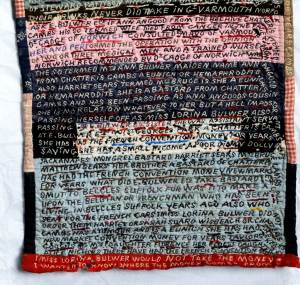

The scrolls are neatly and densely embroidered, and read as if they are perhaps a stream (or series of streams) of consciousness. They are worked in wool on a range of re-used cotton fabrics. Three of Lorina’s scrolls have been discovered, the one cared for by Thackray Medical Museum was created in 1904 and is the latest of the three. The others are held by Norwich Castle Museum where, having a more local connection to Great Yarmouth, curators continue to research Lorina Bulwer’s life.

Lorina’s voice comes through so strongly and authentically in her work that people are drawn in and want to find out more. This was certainly the case at our workshop in Leeds!

Catherine Robins, assistant curator at the Thackray Museum (housed in a building that was originally a workhouse, incidentally), gave a presentation outlining Lorina’s life and focusing on the scroll that they have. Big thanks to Catherine and the Thackray for doing this. Some of the information in this post is taken from Catherine’s presentation.

We learned that Lorina’s family moved to Great Yarmouth in 1861 from Sussex. She had four siblings but by her father’s death in 1871 all but Lorina had left home. When her father died she and her mother went to run a boarding house, until her mother’s death in 1863. The next reference we have of Lorina is in the 1901 census where she is recorded as being one of over 500 inmates at the local workhouse, and one of 59 registered to their lunatic asylum. Lorina remained there until her death in 1917.

We learned that Lorina’s family moved to Great Yarmouth in 1861 from Sussex. She had four siblings but by her father’s death in 1871 all but Lorina had left home. When her father died she and her mother went to run a boarding house, until her mother’s death in 1863. The next reference we have of Lorina is in the 1901 census where she is recorded as being one of over 500 inmates at the local workhouse, and one of 59 registered to their lunatic asylum. Lorina remained there until her death in 1917.

On censuses prior to 1901 there were no mental health conditions recorded for Lorina. Contemporary thought was that a calm and civilised environment was best for helping those with mental health problems, and perhaps Lorina’s parents and then mother cared for her at home. Upon her mother’s death, then, there would have been no-one to look after her and it is possible a sibling or siblings decided the best thing was to send her to the workhouse.

But we wondered if there was something more sinister going on. Was Lorina seen as a troublesome, unmarried spinster who nobody wanted to live with? Was she sent to the workhouse because it suited the family? We could think of plenty of examples of people, particularly women, being locked up asylums and other institutions – and right up to recent times – for supposed moral failings, on the decisions of men – family members, doctors, psychiatrists, judges.

Someone recommended the books of Elaine Showalter, particularly The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830-1980, which makes a study of how cultural ideas about proper feminine behaviour have shaped the definition and treatment of madness and mental health in women.

The stitching style in the scroll points toward an educated woman from a family which was not poor. So we wondered why Lorina was sent to the workhouse rather than a private institution. No wonder she was angry! Was this anything to do with mental illness or was she justifiably furious? Some of the group thought of Lorina as a loud and angry old woman who refused to be silenced and obedient, challenging stereotypes then and now.

The stitching style in the scroll points toward an educated woman from a family which was not poor. So we wondered why Lorina was sent to the workhouse rather than a private institution. No wonder she was angry! Was this anything to do with mental illness or was she justifiably furious? Some of the group thought of Lorina as a loud and angry old woman who refused to be silenced and obedient, challenging stereotypes then and now.

A lot of Lorina’s anger was directed at individuals – over 70 people are mentioned in the three tapestries and all seem to have existed. Her oldest sister Anna Maria receives a great deal of anger. She also makes reference to mental health, but never her own – she refers, for example, to Mad Molly and other people in the asylum.

It is clear from much that she says that she feels she has been cheated of money and that she distrusts a great number of people. She makes frequent reference to people not being who they seem and to people potentially stealing her identity. Following from this and furthering the sense of injustice, she frequently tries to link herself to nobility and in another tapestry tries to claim she is a relation of Queen Victoria.

Lorina’s work was clearly created to be seen. The scroll in the Thackray Museum begins, “To Lacon Esq Banker Ormesby House Ormesby Nr Gt Yarmouth Please forward this scroll to Rht Hon Earl Bulwer Lytton Knebworth Hertfordshire from Miss Lorina Bulwer Gt Yarmouth Norfolk.”

This raised another set of questions: were Lorina’s pleas heard by anyone? Did anyone outside the workhouse see her work during her lifetime? How come these tapestries have survived? Who might have looked after them – family, workhouse staff? One theory was that perhaps a nurse in the asylum saw some value in the scrolls and took them away. Nursing at that time wasn’t a valued profession and people looking after Lorina in the asylum would probably have been unable to read, which explains perhaps why the scrolls were not censored. They may not have been seen by doctors or others in charge of the workhouse, as they would have rarely visited or taken an interest in life on the wards.

Tapestry production was not common in workhouses, so why did Lorina produce this? Was this the product of a form of early art therapy? – some early asylum reformers had begun experimenting with occupational therapy at the time. However, someone working as an occupational therapist in institutions in the middle of the 20th century has said that sewing was more likely an occupation to keep Lorina quiet – and this was the feeling of our group as well. She may have been sitting quietly, but her work shouts out!

As the scrolls are so delicate, we looked at enlarged projections of Lorina’s work during Catherine’s presentation. We were struck by Lorina’s skill and technique. The stitching is very neat, colours are chosen to contrast with the different coloured background fabrics and while there is no punctuation, the spelling is accurate, with many words underlined. At first sight it looks like the words have been written with pen and ink rather than stitched.

As the scrolls are so delicate, we looked at enlarged projections of Lorina’s work during Catherine’s presentation. We were struck by Lorina’s skill and technique. The stitching is very neat, colours are chosen to contrast with the different coloured background fabrics and while there is no punctuation, the spelling is accurate, with many words underlined. At first sight it looks like the words have been written with pen and ink rather than stitched.

This idea of the scrolls being a stream of consciousness was discussed a lot. There are compelling arguments to suggest the work was planned out rather than just random, but we just don’t know. Clearly the work would have taken a long time to make.

Her mind was working fast, but her methodology was slow.

The time taken to stitch would have led to a break in her thoughts.

She was seeing as she spoke.

The materials used are interesting as it is unclear how she would have got them. Going into the workhouse a person would have had all of their possessions taken and a workhouse uniform given. Some of what was likely the uniform can be seen in the tapestry, but there are lots of other materials including rare, bright colours, perhaps dress materials. It’s possible that asylum nurses brought these in, or that Lorina was allowed to keep some of her possessions on entering the workhouse.

The tapestries have a really contemporary style, and we agreed they are beautiful as well as fascinating objects. There’s a clear comparison with Tracey Emin’s stitched artworks, including her tent, as well as Cornelia Parker’s Magna Carter (An Embroidery), most of which was stitched by prisoners.

The tapestries have a really contemporary style, and we agreed they are beautiful as well as fascinating objects. There’s a clear comparison with Tracey Emin’s stitched artworks, including her tent, as well as Cornelia Parker’s Magna Carter (An Embroidery), most of which was stitched by prisoners.

They are composed like an art work or painting. This is like Mark Rothko’s work.

Thanks to all who came and took part in this discussion. People’s expertise in both history and needlework gave some wonderful insight into Lorina’s life and work.

Thanks to Union 105 for hosting the event, the Co-op in Chapel Allerton for providing refreshments and of course to Catherine and the Thackray Medical Museum for delivering the workshop.

2 thoughts on “Lorina Bulwer’s mind worked fast, but her method was slow”